Untapped potential in a daring, evocative, but ultimately unsatisfying group role-playing game shooter.

Hasn’t the Old West always been strange? A violent fantasy of looting and ruin, bravery and apathy, resurrected in an endless variety of ways over many generations of literature, movies, folk tunes, and bonfire tales. Undoubtedly, video games have led to some unusual developments. Consider the media.For example, the PS1 Wild Arms series by Vision, in which six-shooters are ancient artifacts wielded by select explorers; or Red Dead Redemption’s pre-patch version, with its physics cursed and centaurs that can fly; or the surreal remnants of frontier life you come across while trudging the plains of Where the Water Tastes Like Wine.

The enormous, putrid history of Lovecraft and the company founders’ prior Dishonored games are mixed together with explicit fantastical elements in WolfEye’s Weird West. This definitely isn’t your typical tale about a rootin’ tootin’ cowboy. When you venture into the wilderness, you’ll come across lively pigmen settlements and abandoned towns that appear out of nowhere. Enter the caverns to find scavenging mutants and blue-stone temples where cultists discuss end-of-the-world visions.

Magic is a regular worry: town authorities use bullets and lightning and fireballs. Shops gladly trade in coins and deerskin with ectoplasm and cursed goblets. Amidst the tinkling piano, one moment you’re pressing a barkeep for information on a gang of kidnappers, and the next you’re attempting to make sense of a captured meteor. Quests switch between gritty pulp fiction conceits and ethereal enigmas. The world is split not just between Native American tribes and colonial settlements, but also between groups of witches, werewolves, and cannibals who are all under the control of a shadowy group of people who might pass for game designers off-screen.

Much as its attempts to miniaturize the knock-on immersive chaos of the WolfEye creators’ prior Dishonored games are more laudable than fulfilling, Weird West’s oddity is, in practice,… hit-and-miss. With a smaller team and budget, it’s a brave attempt to recreate the complex nuances of the finest immersive simulators, full of brilliant concepts that fall flat.

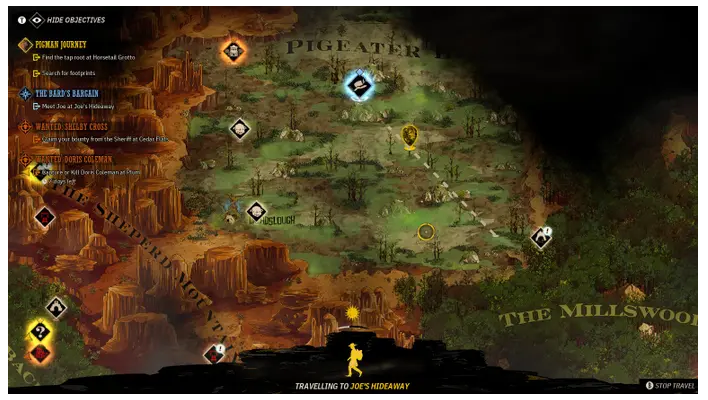

Among these, body-switching is the finest. In a vast, magical experiment with an unidentified goal, you play a member of the previously mentioned cowled Illuminati, who in turn plays several other characters, each with a unique personality that changes chapter by chapter thanks to a magical brand. Starting from disparate locations on the globe map, a gloomy amusement park representing classic North American terrain, every character presents not only a distinct approach but also, hypothetically, an alternative viewpoint and set of dramatic limitations.

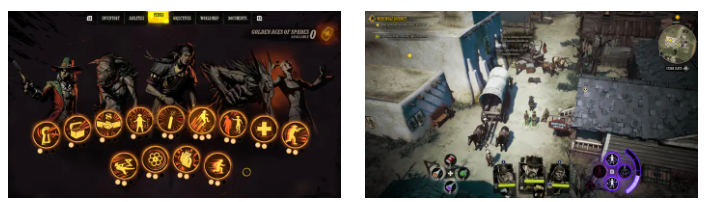

As Jane Bell, an elderly bounty hunter compelled to go on One Last Job when her companion is kidnapped by cannibals, you begin the game. With a focus on AOE abilities and geography traps, as well as the bone relics and shimmering golden cards you’ll need to unlock skills and raise your stats, her tale teaches you the fundamentals of both stealth and gunplay. Think viewcones and hiding in bushes. She also walks you through the game’s morality system and other map features, such as pop-up random encounters and the fact that crimes only damage your reputation if witnesses survive to tell the story.

All this seems quite understandable: a Fallout-style role-playing game set in the Old West with hints of Arkane. However, you are subsequently thrust into the body of the freshly metamorphosed pigman, Cl’erns Qui’g. Qui’g is unaware of his identity, or rather, his past self. It might be challenging to sell your excess stuff because he is, to put it mildly, unwanted in human settlements. Positively, he may regenerate his health by consuming corpses.

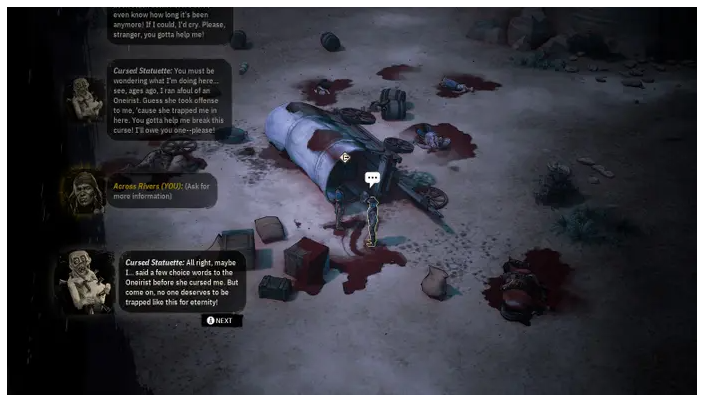

Following Qui’g is Across Rivers, a member of the Lost Fire Nation. These stories are authored by Anishinaabe author Elizabeth LaPensée and are based on actual Anishinaabe indigenous communities. Rivers and his people are portrayed as defenders of the West, sent to find and eradicate the actual avarice that drives colonial expansionism. Aside from supernatural dangers (and allies), he must be concerned about rifts with nearby non-indigenous trapper villages, which you may decide to mend. Desidério Ríos, a quasi-evangelical religion’s messiah and sharpshooting werewolf, is fourth in line. They are on the lookout for something known as the Blood Moon. Theoretically, he is the last playable character’s deadliest enemy. He is a witch novice called upon to piece together the big scheme that has been outlined in earlier episodes.

Naturally, a lot of class-based role-playing games are founded on the concept of viewing the same world via many perspectives. In Weird West, the chaser is a character who shapes the chances for their successors, each of whom must cope with the fallout from the preceding chapter. Naturally, this is most noticeable when it comes to significant story decisions. For example, as Jane the bounty hunter, you may eliminate a certain group of criminals from the game, which will undoubtedly make things simpler for the other characters but may also make them less interesting. However, it also holds true for lesser things, such as villages that are ultimately empty and then refilled with stranger dangers or secondary goals that players pursue together. Former heroes may also become NPCs in your posse, giving you access to their prior belongings. Some people could turn against you, depending on your reputation and decisions.

I’d love to see more games take inspiration from this wonderful ensemble idea. The level maps, which are individually somber Petri dishes approximately a minute wide that curl up into paper at the edges, have a similar bubbling potential. These vary from somewhat active trade centers to desolate farms and cathedrals, and from rotting swamps and graveyards. Mineshafts, ice-locked treasure troves, and forests of incandescent cave fungus are hidden under the surface. Larger communities have general stores, tanneries, banks, shops, blacksmiths, and physicians in addition to one or more story-specific buildings. Outside the game, there are coyotes and deer that may be killed for their pelts, which can be crafted into vests, or for food that can restore life. These maps are rewarding for some thought, even if they’re not quite as complex as, say, a Hitman level. Their residents go about their everyday lives, going to the bar after dark and locking up thereafter; if you want to rob the bank, you should probably do it at night.

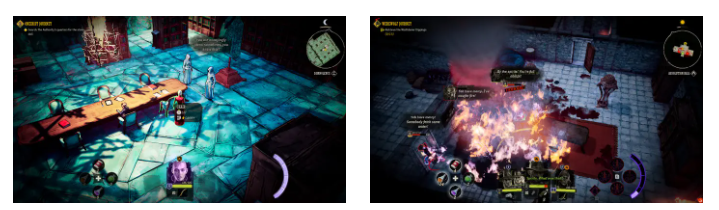

Additionally, most levels are set up to detonate, with flammable oil, poison, or barrels of TNT scattered around to urge you to pull the trigger as you squeeze through the underbrush. The game’s fondness of self-propagating environmental dangers is reminiscent to Divinity: Original Sin, if Dishonored is the topline artistic influence on Weird West, coloring everything from the slashing inks of the character graphics to the singsong wispiness of the music: First Sin 2. Rainwater ignites dynamite by conducting electricity. Oil barrels and lights may be used to create trails for wildfires, which spread in the direction of the wind.

Another variable in the landscape is the dead. Beyond simple strategies like concealing them from view, Weird West has an open curiosity in the various uses of corpses. Every location has a vulture entourage that descends quickly onto the fallen, occasionally obstructing your photos. The majority of communities include a real, operational cemetery. If you visit the site after a shootout, your victims will be freshly buried along with any belongings they may have carried. Although I’m not sure this actually happened throughout my playthrough, the game teases with the possibility that uncovered remains can return as zombies or something worse. You can bury the dead yourself, which I frequently did when playing as the rather respectful Across Rivers.

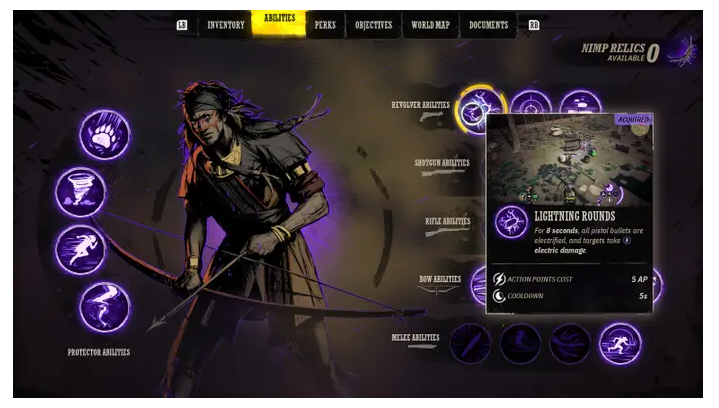

Plenty of possibilities! However, despite some excellent set pieces, such as the previously mentioned ghost village, Weird West finds it difficult to fully use all of these opportunities. The top-down perspective and the graphic book visual design may be the first red flags as they frequently squish and hide the ingenuity of terrain configurations while turning the object gathering into a complete annoyance. Beyond their story setting, the cast also seems a little stifled. They are each given four unimpressive skills that are not particularly noteworthy on their own and provide no foundation for a playstyle. There are also few combination options and no modifiers to unlock.

The most obvious characters are the pigman and the witch: she is a hacker duellist with the ability to teleport, absorb bullets for health, and summon ghostly clones as diversions; he is a brawler with rushdown skills and an AOE stomp. The rest are like everyone’s clumsy initial attempt at a Skyrim build. Jane Bell is skilled at luring people into her improvised traps or making them like her for ten seconds at a time. Across Rivers is unable to determine if he is a D&D shaman summoning spirit bears and (enjoyably unexpected) tornadoes or a sharpshooter speed-walking through the bushes. Worst of all, werewolfing is really a glorified melee power-up. Desidério the werewolf is actually a confused cleric with heals, buffs, and team-wide invisibility spells.

More thought will go into weapon abilities such as lightning pistol rounds or quiet rifle shots, while less thought will go into passive benefits like quicker reloading or higher leap height. Characters eventually blend together due to these latter possibilities, which are shared by the whole cast. However, you must re-unlock weapon abilities for each chapter, which encourages you to try out other strategies.

A few unimpressive special moves would do. More importantly, Weird West fails to fully use the many and uniquely limited perspectives that every character offers on the society and environment of the game. The most interesting part of the pigman’s tale is spoiled early on when he receives a mission that makes him acceptable to the people in the town. Because there is no lunar cycle and no need to worry about things getting hairy when you’re attempting to (e.g.) sweet-talk the sheriff, you can play out the whole werewolf storyline without ever changing into a wolf. The capacity to converse with straying spirits is something that Across Rivers ultimately acquires, although during my thirty hours of playtime, this was primarily used as the foundation for extra fetchquests of the “find my favorite hat so that my soul may know peace” kind.

While the maps are beautiful dioramas, you seldom need to truly look for alternative ways to accomplish goals due to their dinkiness. The typical imsim propagation of stealthy or covert strategies is there – slink across the tall grass! Scale a drainage vent or a window! Arrange a complex multikill by toppling barrels of oil! All the options seem overly accessible, with an excessive number of them per square inch of the screen, and none of them very intricate or creative. At times, the game gives off the impression that it is extremely anxious about players being lost; for example, most guards will probably have a key if a door is locked. Talking your way out of a predicament is an option from time to time, but it’s seldom more daring than making a single dialogue choice—a shame, considering the period bravado and brevity of Weird West’s writing.

The most satisfying method is usually gunplay, but this is harsh praise because gunplay consists of half aimless blasting in the hopes that exploding oil barrels will take care of the rest, and half circle-strafing while spamming the game’s odd but reliable bullet-time dodge. Throwing objects at Weird West makes for a generally more exciting spectacle, in part because the background systems have the customary immersive sim tendency to go a little crazy.

The way the components of this game come back to haunt you is both heartbreaking and energizing. On the other hand, certain components seem to be still trying to figure out where they fit into the picture.

An obligatory “grenade rolled down the hill” anecdote: in a loose homage to Shadow of Mordor’s Nemesis system, foes who manage to elude your rampage may develop grudges. I once murdered the bandit commander when they ambushed me. A guy fled, threatening severe retaliation, which he eventually materialized to exact around thirty seconds later. After I murdered him, someone else fled and promised to exact dreadful revenge, which they eventually carried out, and so on. Though I know there’s no minimum cooking time for revenge, I do enjoy a little anticipation when it comes to my vendettas. I stumbled across someone robbing someone else, which put an end to this conga line of revenge bouts. I caught the robbers off guard and killed them all this time, preventing more attacks. The victim spoke with me and expressed gratitude, all the while shooting mental arrows into my skull. The frontier has difficult ways of living.

Generally, the AI exhibits that well-known mix of being wonderfully oblivious and extremely watchful, responding to things like overturned pails as if a circus were in town and then promptly forgetting about it. I later killed a big bunch of characters by pretty much throwing all of my explosives on the floor and ran out of a cellar. Upon returning later to get the prizes, I learned that the lone survivor had taken up residence in the adjacent bedroom, experiencing moments of intense agony every time she strolled by and came across a pile of burnt bodies. I lacked the courage to step in.

It’s a loose ends game, Weird West. It has an edge in terms of its unscripted storyline and world components. Consider the woman in the basement. As I crept up on her, I realized that she was, in fact, a real person with a past. Just a few hours earlier, I had discovered the missing friend’s abductor in a different town located far away on the map and assisted in bringing her and him back together. The way the components of this game come back to haunt you, given a sufficient amount of time, is both tragic and energizing. Some components, on the other hand, seem to still be looking for their piece in the puzzle, their potential exploding like rain-soaked dynamite. A little more time, I believe, is what this eldritch vision of North America’s colonization could have done with.