A sweet dream come true – OlliOlli World review

It took place at the Logfolk Graveyard. Honestly, a plaque ought to be there. I can intuitively recall the precise point in a game where time may suddenly become a dazzling, fizzing haze. Up until then, I had been flying around OlliOlli World, always happy, sometimes succeeding, sometimes barely making it. But then the optional challenge of “Advance trick through a Ghost” appeared in Logfolk Graveyard.

I adore ghosts so much. There are alternative challenges in every level here, but that ghost! I came to the realization that I really wanted to advance—that is, cheat through it! I had to do something I very never chose to do in games as a result. I was forced to take a step that seemed to violate a fundamental rule in a game like OlliOlli World. I needed to return. Returning to the training I had quickly completed hours earlier and overlooked, I wanted to fully comprehend these amazing yet terrifying concepts, so I went back to the core of the advanced techniques system. back to enable me to remove them.

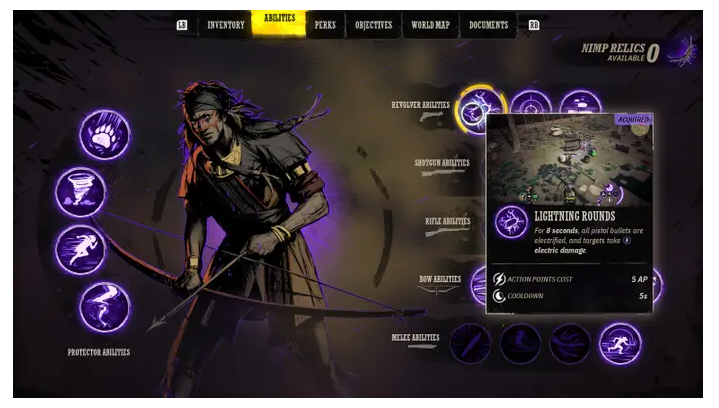

The newest and most outrageous game in the amazing series of 2D skateboarding games is called OlliOlli World. The fundamentals haven’t altered for apparent reasons. Roll7 created a stick-flicking system back in 2014 that appeared to capture skating at the joints themselves—the knees and ankles, as well as the point at which the human body transforms into a living, breathing version of a vehicle jack or shock absorber. To fool someone, you grip the stick and then release it; pick a direction and see what transpires. Are you able to land it? Is it possible to connect it to more tricks? Is it possible to include a grab? Whatever.

Advanced maneuvers, however, expand on it with a hint of Street Fighter 2. Holding the stick, rotate it a quarter of a turn, or more. It is more difficult. Easier to accomplish quickly, as you’re in a hurry here all the time. harder to internalize, at least for me. That being said, OlliOlli’s heart is still, as I mentioned earlier, juddering, beating, and crunching here. Although you may still hit the button if you’re feeling particularly fancy, landing properly is no longer dependent on pressing a button. In other words, even if the push button may have changed locations, this is still a gorgeous thing on wheels.

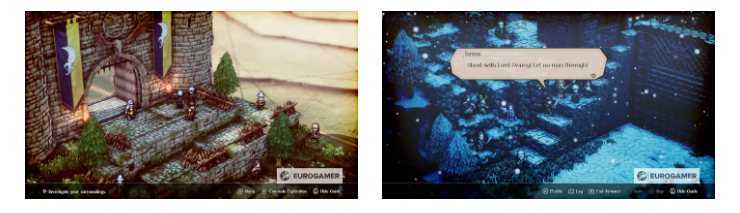

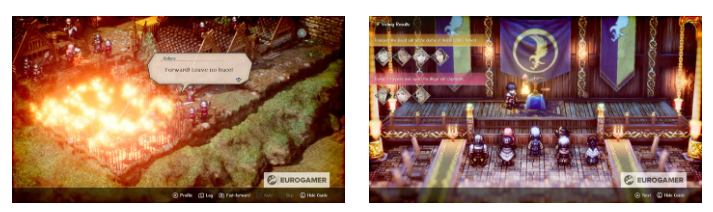

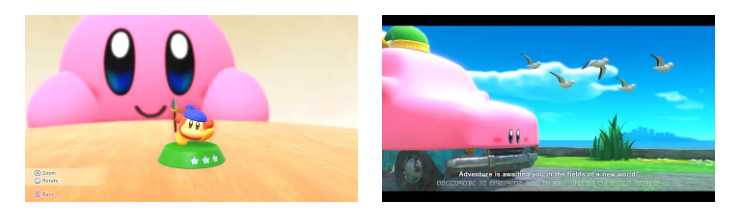

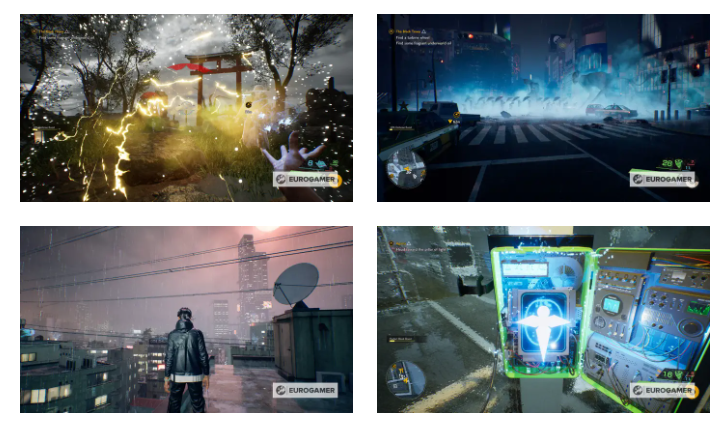

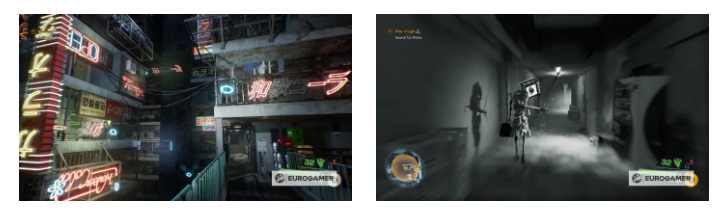

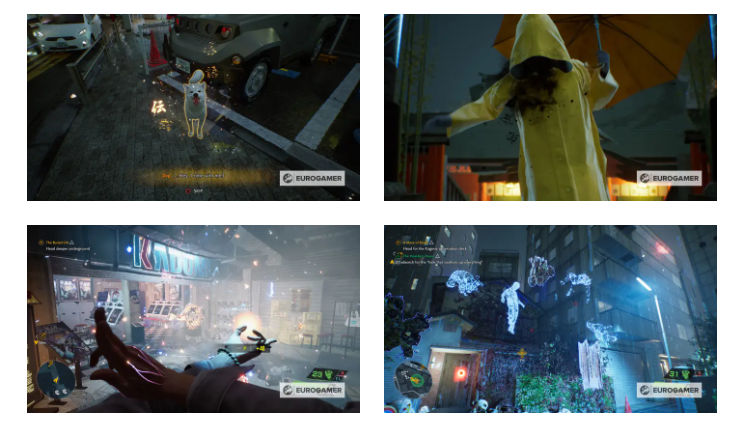

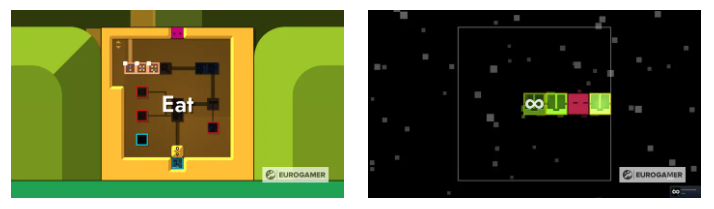

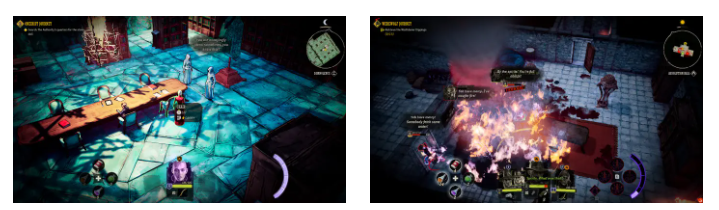

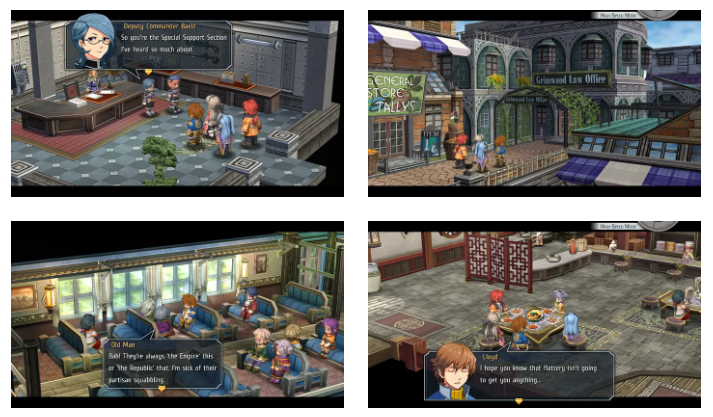

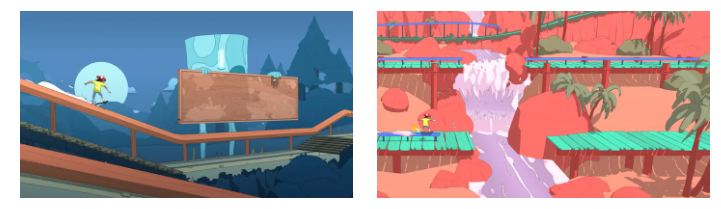

But everything is enlarged! The first two OlliOllis were scrapbook flat, true two-dimensional objects. I believe the first one was pixelart, while the second was slick Hoxton ad agency vectors with Bonanza Bros backgrounds captured at the moment of a picture-perfect sunset. While this is going on, OlliOlli World introduces cel-shaded 3D to the scene. It features wacky, squishy, flappy figures that set off on a wonderfully absurd journey through landscapes that have the color of cartoon ice cream.

Although the universe is somewhat deviant from the 2D plane, the models and assets are 3D. During a run, there will be places when you may change directions, such jumping from one path to another, and sometimes the second route winds around and around the first. Half-pipes that propel you back along the same path but on an other thread will be present. You could sometimes zoom in and out of the screen, but reading will never suffer. Although the game is still divided into custom runs or stages, these stages are connected to form a narrative and a sequence of appropriately bizarre locations that you must traverse.

Pencil drawings merging with cartoon seagulls and thick, oaky woodlands is a wonderful execution. The industrial stage, where you can dodge poisonous sludge and sprint across manufacturing lines while occasionally skating on a moving platform, is definitely my favorite segment. Subsequently, there’s a sci-fi metropolis including some very epic drops and some vicious wall-riding chains. Conversely, the soundtrack has a squidgy, chirpy, cheeky, zappy quality reminiscent to the Wii’s OS music, as performed by Mr. Scruff and Moloko during the Statues era. The ideal music selection for the cocktail room of a Holiday Inn situated above Saturn’s rings, which is essentially where everything happens. More than that, though, are the sounds of moving boards and the gravelly thump of wheels on seamed concrete. An auditory delight. A delight.

A few of the runs stand alone as heart-stopping sequences that combine wall-dashes, obstacles, and grinds in a fitting display of terror and agility akin to Morse code. You already have a game with a great heart: a skateboarding, platforming, memory-testing epic. Add branching paths, creative screen furniture, and new talents – some of them provided shockingly late, like stair-riding – that send you back to earlier courses to reveal new pathways.

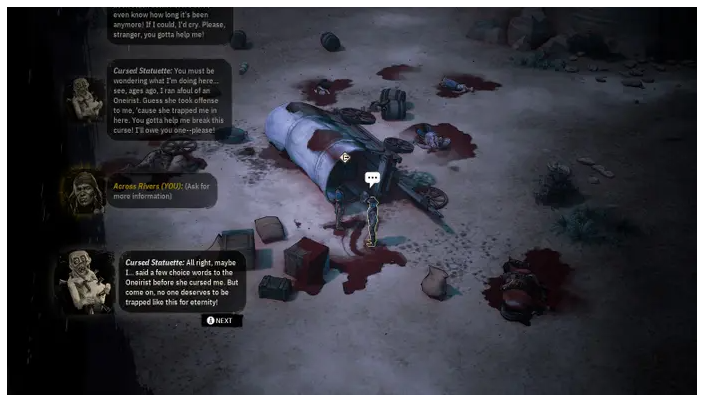

However, since these games are usually two games in one, this is a skate game. One example of this is OlliOlli World, where your initial goal is to complete each level. Then again, don’t you want to advance-trick via a Ghost? Optional challenges force you to view the level you just fought for as a set of new opportunities. Once you’ve passed that barrier, there are endless opportunities all around you in the globe. A combination of set platform obstacles that you must clear and spaces where you may express yourself by doing additional stunts, chains, grabs, manuals, and spins for bonus points make up these two games in one. Those spaces, oh! Locate them! Make them! (Remember them.)

Thus, you elucidate an already complex environment. You explore for potential opportunities. You know, I’m aware of this emotion. (Many thanks to Edwin for priming me for this line of thought with his excellent recent work on warfare systems and poetry.)

This sensation. John McPhee, the author, refers to it as Draft No. 4. He is discussing writing. In a nutshell, because we are now reviewing a skateboarding game, this is what he says: “I put words and phrases in penciled boxes for Draft No. 4 after reading the second draft aloud and rereading the work three times. Draft No. 4 is the one I’m most enjoying right now in this process [by “process” he means writing in general]. I begin looking for more words to put in the boxes.”

Pay attention to the marked boxes. According to McPhee, these phrases “fulfill their assignment but seem to present an opportunity.” I believe that when we replace them, writing typically becomes richer and more really memorable or distinctive. You search for areas where you can perform a little unique task. A ruse. a guide to connect it to an additional maneuver, perhaps including a grab. a sophisticated ruse. Kindness. And the globe begins to widen. The sky has a little brighter sun.

All OlliOllis have this characteristic, but it also connects these games to the broader skate entertainment landscape. Consider Tony Hawk: an area to investigate first, but then an area to change as you go through it. Skate games as a whole are all about this urge to personalize things, to cover them with your human acrobatic scrimshaw. In terms of challenge as well as pure expressiveness, this is the genre to which it is frequently felt that all other genres should strive. In first-person shooters, we frequently choose the crucial route; yet, in skating games, as Oliver Sacks famously stated, we are all destined to be unique people. (It wasn’t about video games including skating.) What could be more prosperous than that? OlliOlli World is the best in its field.

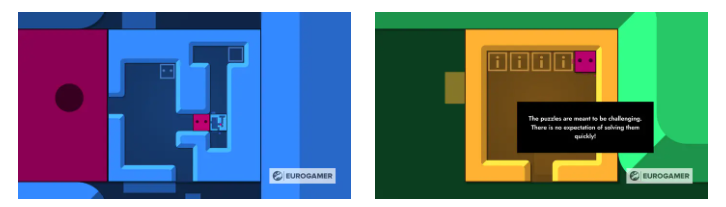

In relation to wealth. Oh, the kind of poetry this game leaves in the notepad of the reviewer: Explore the universe of the small cloud. Triangles in blue. pink forms.

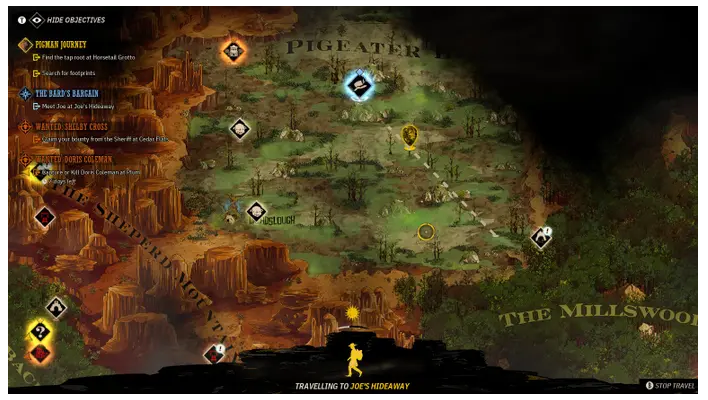

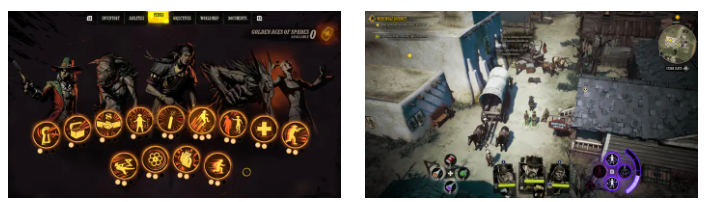

In chronological order: you have access to a few more modes in the cloud world. One allows you to create your own runs and distribute them via a postcode system; it functions much like a procedural generation tool. The other is a league structure that lets you team up with people and score each other as you advance in the rankings.

The stages on the map with blue triangles are optional. The pink forms are optional tasks. The primary goal of each level in the game is to reach the finish without restarting; checkpointing is fair and restarts happen quickly. There are also other objectives to do, and there are normal leaderboards along with “local heroes” who have points for each level they complete. Everything is cartoonish and filtered via pastel colors, which links back to the idea that the game is set in a real world with its own locations, famous people, and a charming narrative running through it all. Not to mention the incredible character builder, where you can always find new goods to unlock and may instantly create almost any type of person you choose by simply pressing the random button a few times.

Draft No. 4. I believe that OlliOlli World is a writing game—or, maybe more accurately, a rewriting game—but that may be because I write. To me, it also serves as a reminder that writing can be subtly tactile. The other day, I purchased a cheap fountain pen from an online store, and the process of using it reminded me somewhat of OlliOlli at its best. Specifically, the sentence! That feeling of shooting over the new paper’s surface and splattering a glossy wake that gradually seeps into the white earth. having some control, but not total control. Not every time. both the audience and the creator.

As it happens, however, this game is perhaps the ideal example of any activity that involves the joyful process of learning, several competency levels to go through, and a plethora of new discoveries to make and try out along the way. similar like writing, really. similar like skating, I suppose. That’s all there is to it: I like this game since it emphasizes exploration and learning. Furthermore, it’s possible that we can always attempt new things and that learning never needs to stop.